a few news highlights

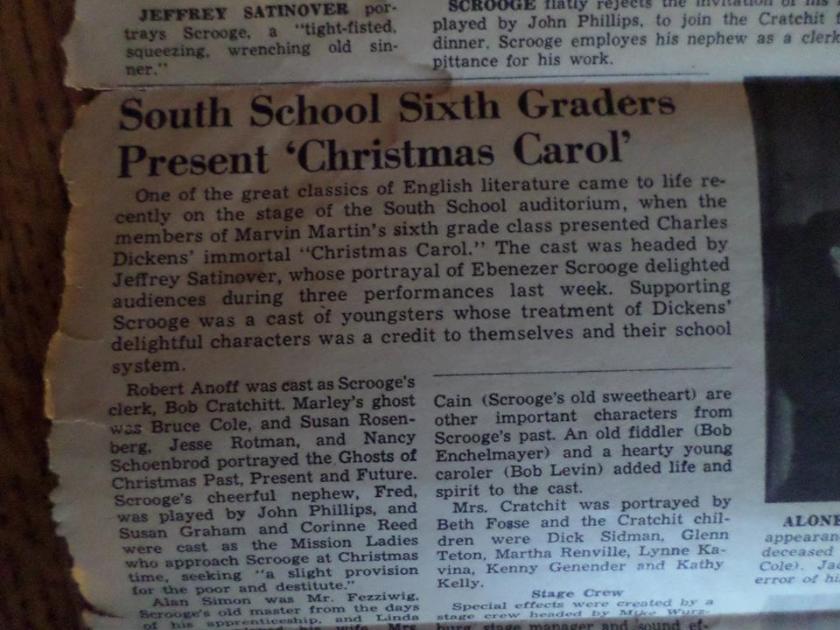

South School Sixth Graders Present Christmas Carol

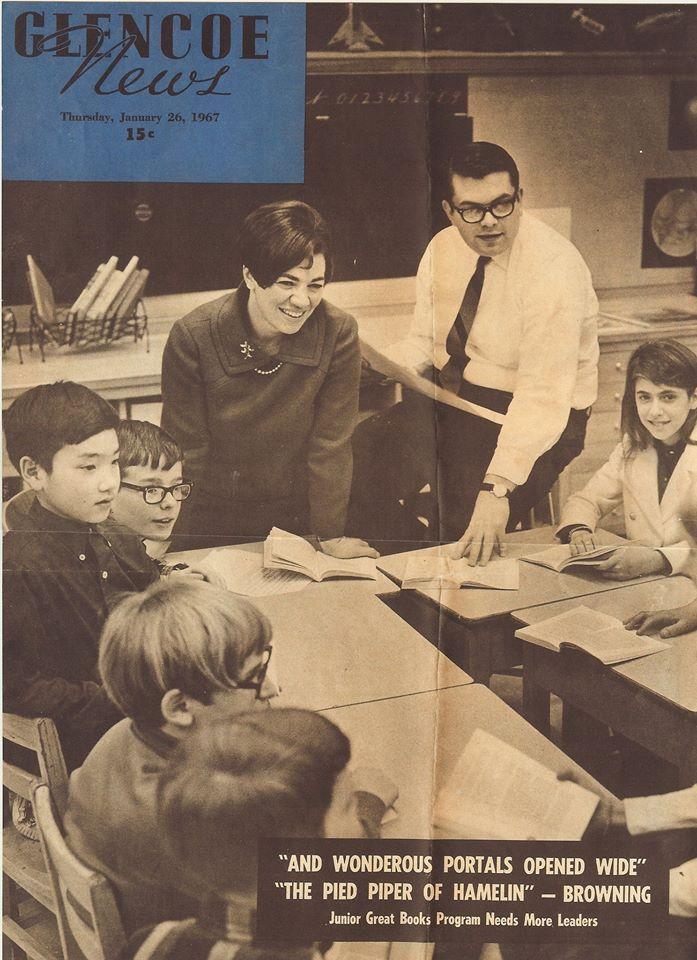

Glencoe News

December 25, 1958:

Curriculum development in the elementary school (Exploration series in education)

Published in 1960

W. Ray Rucker (Author) (he was dean of the National College of Education at the time)

excerpt

Much of the success of Mr. Marvin Martin in developing an interest in literature among his pupils stemmed from his own personal appreciation and its vocal expression. Besides his contagious enthusiasm, he interpreted literature dramatically, as though an actor, and by spontaneous groupings of children for short dramatic sequences, coaching the children to “walk through” a situation and get in the “feel” of it. The children responded with enthusiasm and quick insight. The will to produce a rather finished pageant often emerged from these classroom contacts with literature. Two of such productions take the spotlight in this chapter section. The first of these emerged from Mr. Martin’s introduction of Mark Twain’s Adventures of Tom Sawyer.

Mr. Martin initiated the learning experience on the Tom Sawyer theme by reading some parts of the book to the children. His dramatic expression and bodily movement set the stage for a discussion of the events of the story. He invited several children to come to the front of the room and try out the action suggested by the lines. More discussion was stimulated as suggestions were offered from all over the classroom. Often Mr. Martin asked a child to “Come up and show me what you mean.” He demonstrated some of the action himself, but for the most part he would approach the question of action technique by saying, “If you felt that way, what would you do?” or “How would you look if someone said that to you?”

By this time the children were eager to read the book themselves.

Mr. Martin provided a copy of the book for each pupil and guided the reading for several days, returning again and again to dramatization to illustrate a point or aid in comprehension. During these early efforts to dramatize the story, he encouraged children to try several different roles, to get the “feel” of each character. Gradually, consensus of opinion indicated those children who were best able to portray the various persons in this story. Gradually, also, the idea of developing a project around the Tom Sawyer theme emerged as Mr. Martin and the pupils decided they would like to produce a play from the more important events in the story. Not satisfied to produce a play indoors, they searched for suitable outside locations for reenactment of some of their scenes, and Mr. Bonhivert, head of the audio-visual department of the school district, cooperated with them in making a series of pictures for a photoplay on a film strip. For instance, there was far more realism to the story when Tom Sawyer was able actually to pick a flower between his bare toes in a meadow or sit on the bank of the river and whittle with Huck Finn and Joe Harper. Later these pictures were mounted for display on a bulletin board in the classroom.

This project growing out of children’s literature touched many curriculum areas. The pupils made an intense study of the Mississippi River and its tributaries. They studied land forms, erosion, silting conditions, the delta, effects of floods and deforestation. They learned about conditions of life along the river, including conditions along the Ohio and Missouri Rivers. They found out how people who live near the river make a living. This led to a study of natural resources and industries. All of the social studies activities led to the need for report writing, outlining, note taking, and creative stories and poems. All of these tasks led to further reading, the extension of skill development, and the stimulation of intellectual and aesthetic concerns.

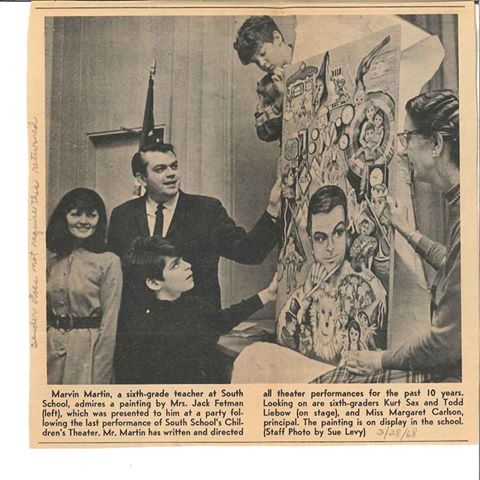

photo with caption

Glencoe News

March 28, 1968

"Adults from many areas of community life will meet for eight sessions with the group's academic director, Edwin Moldof, to learn the art of stimulating intelligent discussion among young readers.The first session will be held from 9 to 11 a.m. at the Glencoe Public Library. Marvin Martin, a Glencoe coleader and Central School 6th grade teacher, explains the purpose and procedure of the Great Books program: "For an adult who enjoys children and finds excitement in a great book, the Junior Great Books Program provides highly rewarding opportunities for adults to share with children in the process of discovery. Adult leaders are trained to guide without indoctrinating. They learn to ask questions which will stimulate thought, encourage discussion, and create issues. They learn to discard questions to which they can find quick and certain answers. The discussions which result are as fresh and revealing to the adult leaders as they are to the young participants." "Junior Great Books discussions," he continued, "provide mutually stimulating, mutually rewarding experiences for adults and children. It is an opportunity for genuine intellectual give-and-take between child and adult."

(TEXT VERSION OF ARTICLE ABOVE)

Christmas Carol’s Special Meaning

Glencoe News

December 25, 1975

“A Christmas Carol” has special meaning for 6th grade teacher Marvin Martin. It was the first play he ever acted in (as a sixth grade Scrooge in Denver), the first he scripted, the first he directed (while also playing Marley, at age 15), and the first play he presented at South School after the new school auditorium was built.

Each year Martin produces a play in which older and young children work together. (First, second, third, and sixth graders, in two casts, are represented in the current production, which completed six performances last week.)

“I don’t really do plays for the end product,” he explains, “but because of what they do for children. A play welds children into a group, brings in those who may have felt left out, helps boy-girl relationships . . . One of the most important parts of growing up is to learn to help younger people. When children can do that--take responsibility, comfort and support the younger ones--they are more mature; it’s part of the cycle.”

“Martin considers a play a seven week project--one week to learn lines--five weeks to rehearse, one weeks for performance.

“All children get parts who want them,” he says, “and that’s nearly everybody. I’ve always written my own plays; about two thirds are based on children’s classics. I like to create a part for a particular child, so I have try-outs first. It’s not type casting, but getting an idea of the range of ability and writing a part which will fit the child. With good casting, directing becomes very easy.”

“I don’t direct too much with kids,” he says. “I like to take them to the threshold of the part, and then let them take over. I take pride in the fact that if two children play a part, they’ll have two different interpretations.”

Costumes are made by the mothers. The scenery is made at school. Martin will wield the power tools and do the heavy carpentry, but the kids do all the pounding and painting.

Sound and lighting effects are quite elaborate. “We have two stereo systems, one for the stage and one for the auditorium,” he says. “Sometimes we use movies or slides. This time we are using a spotlight.”

Much of the special equipment belongs to Martin personally, and he also finances the production as necessary. The children raise money by having bake sales, but Martin has covered anywhere from $100 to $2000 in additional costs for a production.

“The kids really run the whole thing,” he says. “Stage manager, make-up, everything. I’m the most superfluous person around the week of performance, although they always know they can come to me for help, encouragement, or a safety pin.”

He recalled for us some of the plays he has presented since 1958. One of his favorites was “Fractured Fables” which dealt with current problems such as violence in the movies and political corruption like Watergate.

Another was “The Thinking Machine,” in which a professor invents a computer which can pick up brain waves and project thoughts on a screen. Each child in the story enters his own fantasy, and the production incorporated sequences from such classics as “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” “Pinocchio,” “Alice in Wonderland,” and “The Wizard of Oz.”

“The most elaborate production, with 90 children, was ‘The Giant Shrinker,’” says Martin. “It was about the pressures of preadolescence--very fanciful, with terrifically elaborate stage sets and special effects.”

That was the one that cost Martin personally $2,000. It was covered by the Daily News and WBBM and played 16 performances to standing room only audiences.

The plots of Martin’s plays, which characteristically deal with children confronting a problem situation, are usually learning vehicles in themselves. For next spring, he is planning an original Bicentennial play “without a single Paul Revere.” Instead, children will be besieged in a classroom by an alien force which is chopping away at cultural values. The children will have to deal with it, using elements and values of our own country.

While Martin says he has no interest in working in the theater outside of the classroom, he is a dedicated theater buff who “never misses a season in new York.” “I get there to see about 16 plays each year.” He also takes groups of children to New York on theater trips almost every summer.

As for “A Christmas Carol,” which comprises the business at hand, Martin says it is one of his favorites, as it is for so many others. “I think that no finer statement has ever been written about loving and giving and caring about other people,” he says. “There must be thousands of performances going on this year . . .”

And South School must be right up there with six of the best.

Mentioned in these articles-

Arts in the Classroom: What One Elementary Teacher Can Do (p.12)